PRIDE PROTECT PEOPLE chronicled the creative output, ethos, and community of Brisbane’s Goose Goose Ganda Collective (GGG Collective). Jessica Astrid and Mary Alexander established the GGG Collective in 2015. The pair’s friendship and collaboration began in the 90s as both performed in South East Queensland’s queer nightlife scene. The GGG Collective is comprised of artist-performers whose relationships and performance histories span multiple decades.

The cross-generational collective filled POP Gallery with a raw assemblage of costuming, protest, and performance ephemera, shrine-like altars to Pride figureheads, textile works, video installation, and portrait photography. The exhibition itself was solidly rooted in Brisbane’s queer community but also draws lines to the North American Pride movement as part of a lineage of civil rights protests. It was a grassroots counter to what Pride now feels like for many: commercialised, corporate, diluted, and obedient in its aims for acceptance and assimilation. In PRIDE PROTECT PEOPLE, the Collective roused a call to action by reminding visitors that Pride’s inception was a riot—the Stonewall uprising—and, as a refutation of cisgender heterosexual hegemony, queer identity is inherently anti-authoritarian.

Alexander’s alter ego, drag king Tricky Boom Bang, is a long-haired ‘bogan rock god,’ pith-hat- and safari-suit-sporting lothario in Vagina Hunter (2017). Looking past a shroud of a pink fabric labia, Tricky peers at the viewer with gleeful derangement, suggesting his pride of place comes from an intimate knowledge of the genitalia. Performing in the gallery on Stonewall Day, Tricky stalked through the crowd with a magnifying glass, inquiring after the ‘elusive vagina,’ before disappearing inside a two-metre-tall, voluminous pink wrap, as if birthed in reverse. The work is at once horny opportunism and a play on colonial exploration.

Alexander’s drag arose in response to social pressures to present as either butch or femme, and the separation of the lesbian and gay communities in the 90s. She uses gender performance as a vehicle to explore identity, challenging binaries by celebrating an individual’s internal diversity.

Throughout the exhibition, Alexander also employed appropriation in her collaborations with her late partner, Hillary Green. Green’s WBBT (2013) playfully depicts the pair cosplaying as Jean Michel-Basquiat and Andy Warhol. Posed as monochromatic boxing rivals in gloves and satin shorts, Green’s topless Basquiat directs a robust stare at the viewer whilst Alexander’s impish Warhol remains swaddled in an emblematic black skivvy. Just as Alexander’s Tricky rejoices in being found in Vagina Hunter, the subjects in Green’s photographic portraits are distinctly aware of being perceived.

Green’s tongue-in-cheek BLAC By Popular Demand series (2013) features the artist as six African American stereotypes who also return the viewer’s gaze. Dante is a stud lesbian modelling a blazer and scarf ensemble, evoking Shane from The L Word, and with the addition of a glittery purple dildo, peeking through her trousers. Carter Washington spoofs Samuel L. Jackson’s Jules from Pulp Fiction, and in No Cents the artist postures as the quintessential gangster-rapper. Meanwhile femme subjects including Honey Brown, Zemundi, and Freaky Tranique present conventional poles of femininity. Brown and Zemundi cross their arms, appearing demure and composed in modest dress and traditional garb, whilst underwear-clad Tranique holds a deep squat that suggests sexual availability. Green is aware that these stereotypes register with white Australian audiences. The work is not simply a play on the multiplicity and fluidity of personal identity; it also demonstrates how the mass media denies personhood, offering stereotypes in lieu of minority representation.

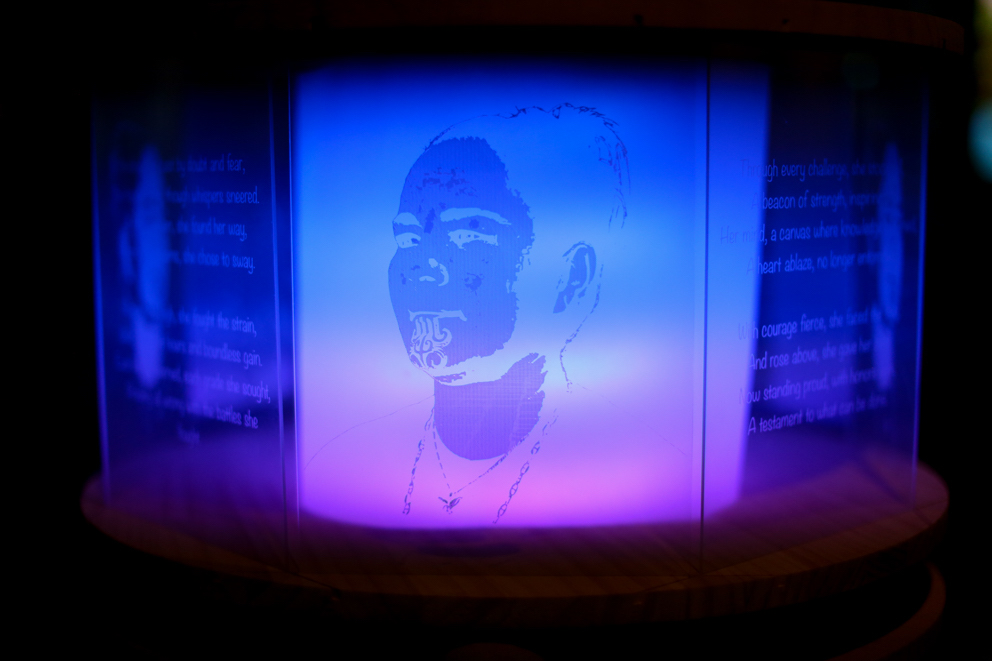

Minority groups often forge close-knit communities as a matter of survival. The interweaving relationships that constitute the Collective were at the core of PRIDE PROTECT PEOPLE. A salon hang in the exhibition of works from the GGG Collective’s personal collections was cheekily titled Heroin Wall (2023). This exhibition centrepiece paid reverence to queer and BIPOC creators including Troy-Anthony Baylis, Gerwyn Davies, Karla Dickens, Tyza Hart, and Luke Roberts.

The Collective also demonstrated solidarity with international postcolonial struggles. Astrid and Libby Harward’s video installation, Like Water (2023), confronts the senses with bright lights and the sounds of clashing crowds, protest chants, and firing gas canisters. Screens and projectors perched on large orange water barriers played Astrid’s footage from the 2019 Hong Kong demonstrations, whilst the creation of a small, enclosed space mimicked crowd control tactics. Here, the GGG Collective posited queer liberation in partnership with colonial liberation, in Astrid’s words: “protest as a reaction to acts of violence, not an act of violence in itself.” Moreover, this work speaks to the broader histories within which PRIDE PROTECT PEOPLE exists.

To construct a local Pride narrative, the GGG Collective wove symbols of North American Pride into Australian folklore. In The Battle of Stringy Bark Creek (2023) and MPJ Saint (2023), Astrid and the GGG Collective drew parallels between Ned Kelly and Marsha P. Johnson as symbols of dissent and liberation. Visually these works echo one another. Displayed along perpendicular walls of the gallery, the red-stained hessian saddle bags of Battle mimic the brown cardboard boxes of MPJ, the latter sprayed in red with the titular three letters. For some Kelly Gang admirers, these two figures might seem at odds, but the alignment resonates. Johnson—a black trans activist, founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, and prominent figure of the 1969 New York City Stonewall uprising—used money made from sex work to establish a shelter for homeless queer youth.[1] Kelly—a notorious bushranger of the late 19th century— infamously penned a manifesto denouncing the police, the Victorian government, and the British Empire, demanding justice for his family and the rural poor. Reminders of Pride’s origin as a spontaneous act of defiance against violent raiding police are peppered throughout the gallery.

Armed Police Escourt (2023) is a deadpan statement by the Collective on the presence of police at contemporary Pride marches. In 2016, after a 25-year ban on Queensland Police Service (QPS) officers marching in uniform, an invitation was extended to the service on the condition that uniformed officers march unarmed.[2] As shown here, jubilant officers marched down Brunswick St toting large QPS flags and miniature rainbow flags while armed tactical officers flanked them solemnly. At the time, news outlets cropped press photographs to omit the armed escorts. By re/presenting the uncropped photographs, the Collective underscored their belief in Pride as protest. Meanwhile, Astrid’s large riot shields loomed from the gallery’s windows and ceiling, conjuring the threats referenced in Clare Callaghan’s works of oppression and survival.

Callaghan’s soft sculpture triptych amplifies a sense of arduous and repetitive labour. Small discarded objects, such as buttons and sequins, are individually stitched onto scraps of frayed and distressed denim using fragile horse-hairs. Denim, a fabric associated with counterculture and blue-collar work, was often worn by gay men throughout the 20th century as an expression of masculine virility. Denim jeans’ back pockets evoke the coloured handkerchiefs of cruising culture, whilst garment flies and seams conjure thoughts of undressing and ensuing intimacy. Each of Callaghan’s works feature a word in relief: “Work,” “Bait,” and “Rage.” Pay It No Mind (2023) (“Work”) speaks to the work of survival, the invisible labour of living through systemic oppression. Lineage (Mother of Pearl) (2023) (“Bait”) refers to the history of police officers baiting gay men for arrest and beatings by posing as homosexuals. Finally, Work on Progress (2023) (“Rage”) asserts the embodied rage provoked by such experiences. There is a tenderness and intimacy in this work that radically contrasts with the acts of violence it represents. Coupled with costumes, performance, and the jewellery of Sarah Murphy, PRIDE PROTECT PEOPLE proffered bodies as potential sites for protest and agency. On Stonewall day this was extended with the invitation to audiences to stamp their own name, or that of loved one, on jewellery.

José Esteban Muñoz applies a utopian lens to queerness, writing: “queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future.”[3] In PRIDE PROTECT PEOPLE, the GGG Collective drew from local and international pasts to construct a nebulous, liberated future. The exhibition married the chaotic ferocity of protest with a spiritual reverence for community. Soft undertones of bodily encounters and relationships intercut the brutality of the violent histories recounted. Throughout the exhibition, the GGG Collective suggested protest as a vehicle for self-determination and collective mobilisation as a source of power. In doing so, the Collective pulled together a rebellious exhortation that articulated the gritty foundations of Pride in a distinguishably Queerslander voice.

This review was kindly made possible with funds from Lemonade Review Sponsor, Kellie O’Dempsey. Contact Lemonade via editor@lemonadeletters.com.au to sponsor a forthcoming review.

[1] Emma Rothberg, “Marsha P. Johnson (1945–1992)” National Women’s History Museum. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/marsha-p-johnson

[2] Nerelle Harper, “QLD Police Finally Allowed to Join Brisbane Pride March in Uniform After 25 Years,” Q News, 31 August 2015. https://qnews.com.au/qld-police-finally-allowed-to-join-brisbane-pride-march-in-uniform-after-25-years/

[3] José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009). https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/literaturetheoryandtime/ltt-crusing_utopia.pdf

This review was kindly made possible by Lemonade Sponsor, Kellie O’Dempsey.

Julia R. Anderson is an emerging arts worker and musician based in Meanjin.