The Art of Banksy: “Without Limits” in Queens Plaza is expansive. It presents an array of Banksy’s most recognisable works in the form of originals, replicas, and re-imaginings. Reading didactics while sandwiched between David Jones and Chanel, I was struck by the feeling of being in a microcosm of the arts industry, confronted by a dissonance between its mythology, idealism and commercialism.

Banksy inspires an impassioned response in many. For some, he is a working-class champion, a punk rebelling against the arts elite through pranks and unauthorised street art, an artist-activist highlighting social issues. For others, he is an outdated meme of counter-culture. It is hard not to be affected by these narratives when viewing The Art of Banksy.

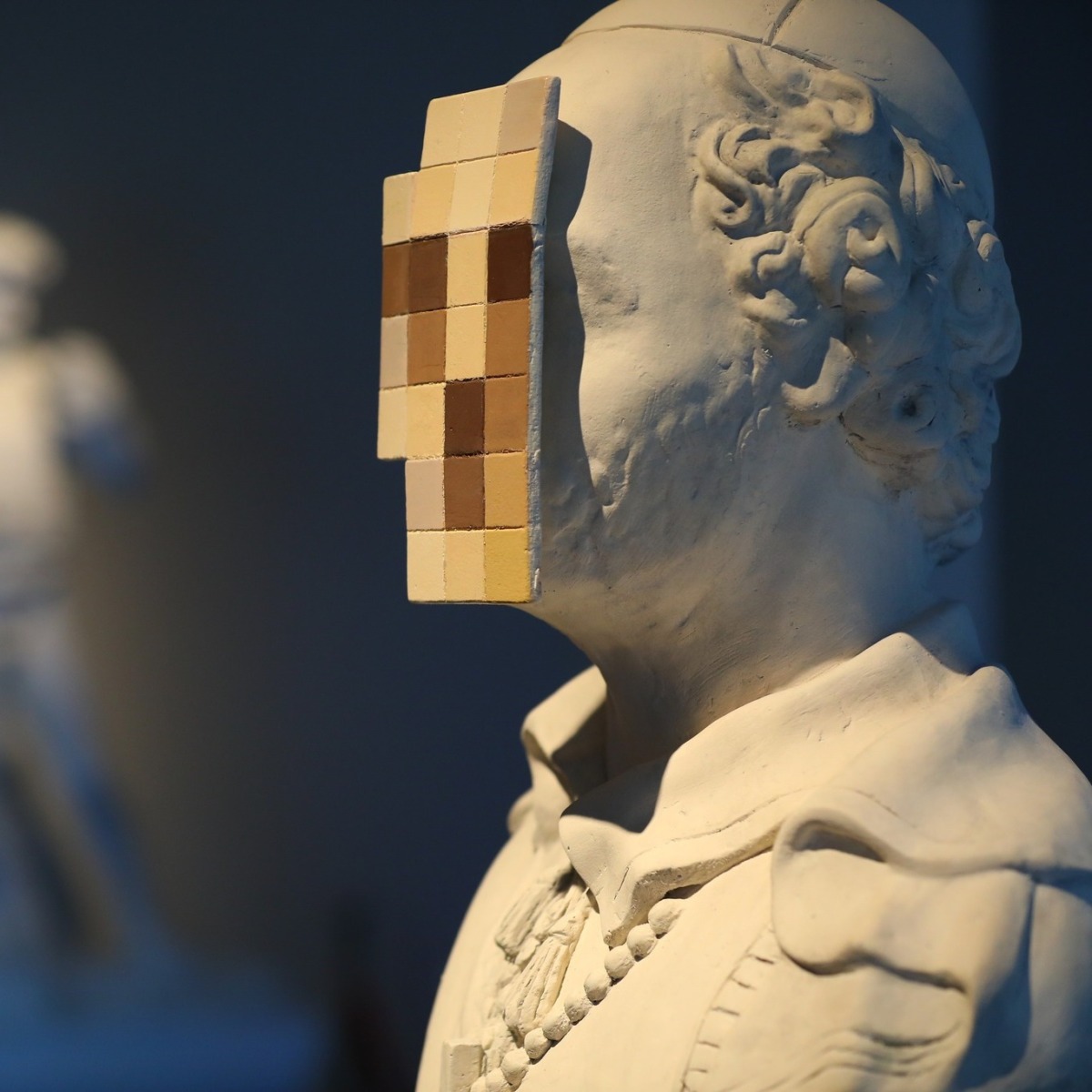

The working-class artist hero trope is prevalent throughout art history, steeped in the politics of identity and authenticity. And throughout The Art of Banksy, the artist’s mythology is emphasised. Organisers also explained a desire to bring his art to Brisbane to call attention to the socio-political issues it concerns. But among such topics, the exhibition’s didactics are also filled with allusions to famous artists and details of value and scarcity. In this exhibition, one is constantly made aware of an artwork’s commercial worth. It’s jarring to hold onto these thoughts whilst simultaneously being assured of the work’s punk, subversive, and deeply political foundations. The monetary value of the works sits at odds with the supposition of Banksy’s working-class relatability. It also begs the question: am I actually looking at an extremely rare and valuable original Banksy artwork, alone in a gallery, with little to no invigilation?

The touring exhibit is itself controversial. Ire is directed largely at the replica works. Banksy supporters called for boycotts on social media after the artist denounced it and similar shows as “FAKE,” operating without his consent, on his website. This concern isn’t aided by the vagueness of marketing on the exhibition’s ticketing portal, which spruiks: “more than 150 of the artist’s works such as certified originals, prints, photos, lithographs, sculptures, murals, and video mapping installations especially created for this tour.” Denouncers are protective against companies profiting from Banksy’s work without his approval. But one wonders whether the artist’s condemnation is only a matter of integrity and not also a financial consideration.

Opposition to authoritarianism is the crux of his ethos, but he is increasingly usurped by the machine of his own success. The confines of a commercial art space naturally blunt the edge of his street art. With the aid of auction houses and institutions, Banksy’s mission statement is radically imploding. Such an ideological threat calls for a creative shift, a pivot in his practice to side-step its own commodification. Banksy’s self-shredding print stunt, which took place at a Sotheby’s auction in 2018, might be one such attempt. However, in this exhibition of mainly two dimensional works, rebellion feels hollow. This is political street art that falls short of provocation; a demonstration of the diminishing returns of punk.

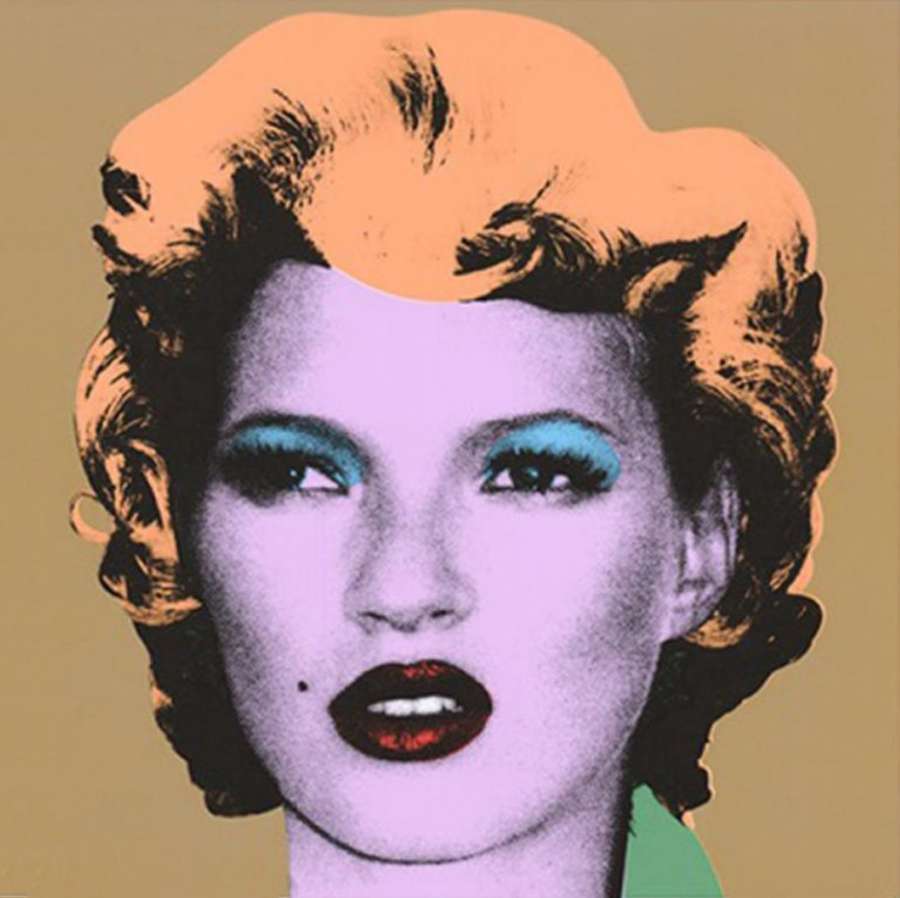

In works such as Soup Can (Violet-Orange-Mint) (2005) and The Painter (2008), Banksy refers to the Western art canon, comparing himself to Warhol and Velazquez. Appropriating the latter, Banksy takes aim at feminine beauty standards and plastic surgery in Venus (2006), uses an image of Mother Teresa for a cynical and cautionary tale of skincare in Mother Teresa (2006), and makes a gendered critique in True Love (2006). Poignant Postmodern references are glaringly omitted by both Banksy and the exhibition. For example: Barbara Kruger’s use of mass media imagery and graphic text, to which Banksy’s work is so politically and aesthetically aligned. Similarly, the Guerrilla Girls’ anonymity, humour, and unauthorised posters are incredibly relevant. This prompts the question of why such artists’ names haven’t been invoked.

Banksy’s work isn’t in conversation with this history of institutional criticism. As a result, his visual language is anachronistic. It invokes Warhol but doesn’t add to the conversation. In Kate Moss (Gold Apricot) (2005)—a take on Marilyn Diptych (1962)—Banksy replaces Monroe’s image with Moss’, though Moss is not a particularly apt stand-in for the late actress. Perhaps Banksy reveals more about his views on women than his engagements with art and its criticisms by suggesting the two are interchangeable?

This isn’t to say Banksy is entirely ignorant of gender and identity politics. Indeed, the plight of marginalised groups is depicted throughout this exhibition. Unfortunately, I often felt unaffected by Banksy’s work, even as a card-carrying member of some of these groups. Banksy’s political themes aren’t necessarily lacking principle, but they do feel reductivist. White male subjects are relegated to the roles of soldiers and cops (CND Soldiers (2005), Flying Copper (2003)); women are vain (Happy Shopper (2009), Venus), or victims (Valentine’s Day Mascara (2003)) and children index innocence (Bomb Hugger (2003)). Meanwhile Applause (2006) and Napalm (2004) attack America’s mass culture and industry of war.

The issue to me is that Banksy’s political statements are so ubiquitous now that they have been rendered redundant. Social media has proliferated socio-political awareness. The suggestions that Britain is classist and Capitalism is bad are no longer a contentious thesis. Moreover, these conversations were initiated and explored more in depth by many of the street and Postmodern artists that precede Banksy. Is this work pushing the envelope in the way punk set out too? I don’t think so. But perhaps such political statements are subversive to wealthy Banksy collectors.

The most refreshing work in the exhibition is Dismaland. It recreates an installation-filled festival, which took place in England in 2015 on the site of a twisted theme park and in collaboration with 50 international artists. On show at The Art of Banksy is video footage of this earlier event, a recreation of the park’s Disney-meets-McDonald’s archway, and ephemera including souvenirs.

To enter the work, black felt pen on crisp white cardboard panels delineates fake security apparatus (including cameras, metal detectors and x-ray) after Bill Barminski’s Dismaland Security Entrance original. Uniformed security guards perform airport-style inspections on visitors as they approach. The theatricality of this work and its ability to collapse the rules of the space posit a titillating social awkwardness. Pricey premium tickets offer further participation, providing visitors a Banksy stencil to spray onto a t-shirt.

Banksy’s success in reaching a large audience and making art feel accessible is undeniable. This is due in part to his critique of the very art culture to which this article belongs. Admittedly, it feels good to have your opinion validated and reflected in the art and culture you consume, and Banksy facilitates this for a large audience perhaps otherwise alienated in art spaces. However his political statements are so sweeping and generalised that they resonate broadly only because they challenge so little.

Here, I’ve suggested that Banksy’s work reaffirms widely-held beliefs in 2023, yet despite the criticisms I’ve levelled at him—by probing the politics behind a masculine art provocateur and his wealthy collector(s) to a Lemonade audience—haven’t I done the same?

Julia R. Anderson is an emerging arts worker and musician based in Meanjin.