The National Gallery of Australia presents the 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial with an intimate touring exhibition on display at The University of Queensland Art Museum. Developed by Arrernte and Kalkadoon senior curator Hetti Perkins, the exhibition is titled Ceremony.

Iteration is a core concept of Ceremony. The exhibition presents Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture from the perspective of First Nations artists, exploring and illustrating how ceremony is at the heart of so many artistic practices, as well as at the intersection of culture and community. My initial thoughts as I walked through Ceremony at UQ Art Museum centred around these themes. It has been a while since I visited a major exhibition. Attendance has been sporadic due to COVID and for other reasons. The continuation of spiritual and cultural maintenance depends on ceremonies. As I viewed the exhibition, I was reminded of this process. The experience of participation and engagement in exhibitions is a kind of ceremony in and of itself. My experience was historical, traditional, environmental and political.

The snapshot of the major exhibit from Canberra begins with a set of shields created by Ngemba artist Andrew Snelgar. Creating art from land not traditionally his own, Snelgar is inspired by where he lives. It was something I could relate to after recently visiting Biripi country around Taree on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. His organically coloured shields display distinct individual designs, with the portrayal of song lines expressed throughout the work influenced by Yaegl tradition custodian Michael Laurie. It was great to see the preservation of a cultural practice sometimes believed to be absent or lost from these areas.

The shields lead you into an exhibition space themed in tradition and reflection. A short film portrait by Gutinarra Yunupinu invites you to the sea, on the artist’s coastal homeland in north-east Arnhem Land. It shows a healing process of ochre being solemnly removed with salt water in a representation of the tradition and ceremony of sorry business. As Yunupinu explains “When a person passes away, Gumatj men and women paint themselves with yellow ochre and white clay on their foreheads, representing the spirit being.”[1] As a deaf artist, the use of new technology is important for Gutinarra Yunupinu in creating a contemporary expression of his culture.

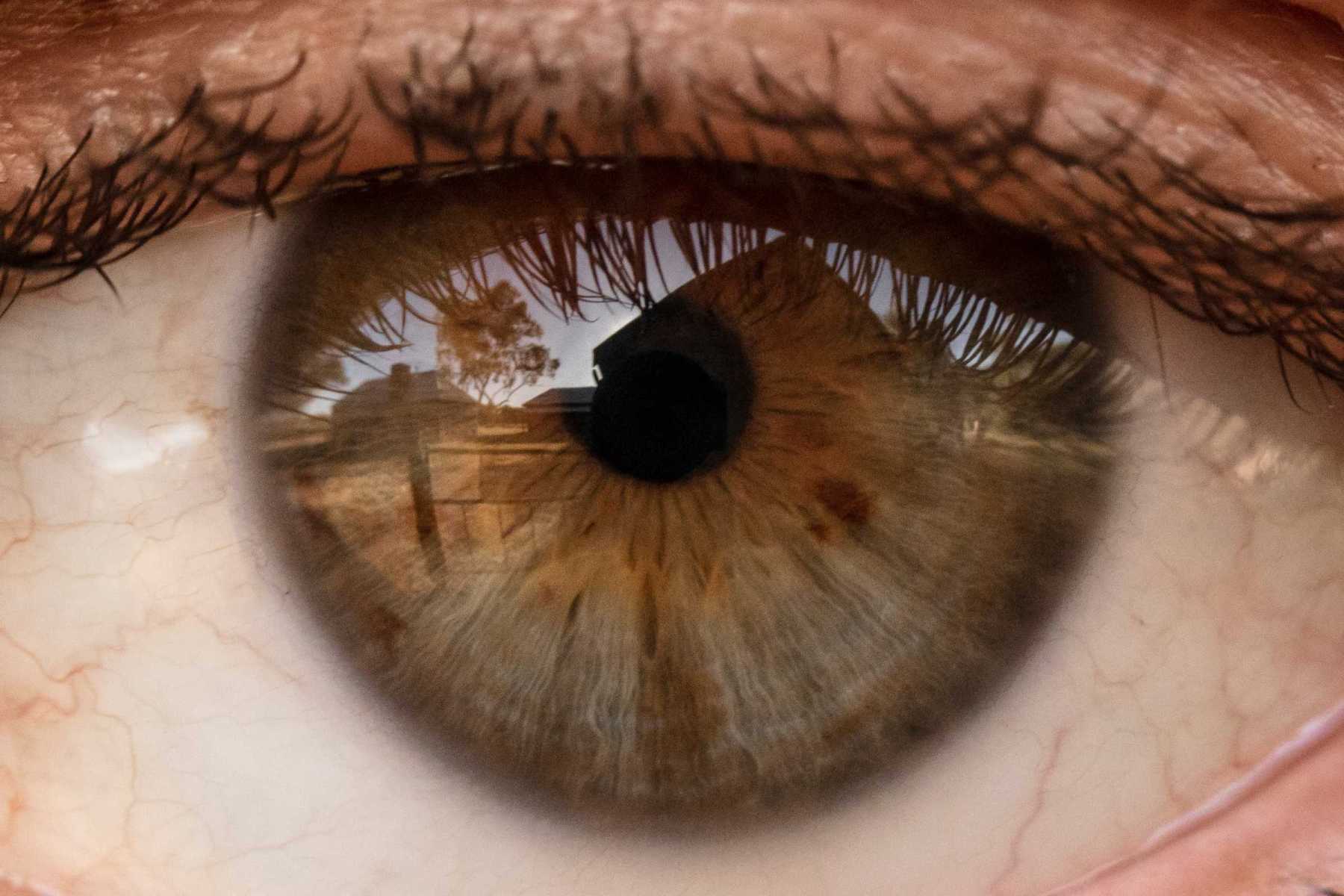

On an opposite wall Untitled (Bungalow) by Dylan River reflects a contemporary lens of First Nations culture and circumstances through photography. The reflection of a bungalow in a close-up of the artist’s eye is a gaze upon the colonial and religious impacts on First Nations people. It speaks to the experience of his Grandmother who as a child was placed in The Bungalow in Alice Springs. As a contemporary artist, Rivers offers an alternative view of First Nations history unlike the black and white staged studio photographs found in museums and libraries.

Walking through the exhibition continues the ceremony with a connection to nature and to the environment. Black is at the fore of various works from traditional cultural practice to the protocol of caring for country. Art admirers may be used to seeing dillybags adorned with colour dyes and bird feathers. It is striking to see the set of black dillybags woven by sisters Margaret Rarru Garrawurra and Helen Ganalmirriwuy Garrawurra. Using natural black dyes as the major part of the creation process is the sole traditional right of both Rarru and Ganalmirriwuy, and they do so as Rarru states, “because black is beautiful.”

The slight scent of burnt ashes accompanies the black embroidery of Banksia trees covering a wall. The ceremony for Gamilaroi artist Penny Evans is the weaving of a physical connection to country into her work. Drawing from the traditional practice of bush management, Evans uses Banksia trees to suggest the “symbiotic relationship to fire developed over millennia.” The fragility of nature on display is strengthened by Evans’ inclusion of a red and orange glaze embedded into tree pods to represent the DNA of Aboriginal people and culture.

A narrative that counters colonial acquisition runs through the works of S.J Norman’s Bone Library and Kaurna artist James Tylor’s piece, The Darkness of Enlightenment. Both artists create works that are a reclamation of language: firstly, Norman in an anthropological-type indexing of language engraves Aboriginal words on animal bones, while Tylor tells a story about the transfer of Aboriginal languages on the frontier.

The exhibition concludes with a ceremony of politics and protest. Blak Parliament House is a multimedia installation. It is a collaboration between members of the Aboriginal-run Yarrenyty Arltere Artists and Tangentyere Artists art centres in Mparntwe/Alice Springs, Northern Territory.A colourfully hand-sewn and hand-made model of parliament house is surrounded by protest signs to address its opening in 1988. As I peruse the work, a passing comment of, ‘It’s not our fault’ from a non-Indigenous Australian visitor makes me sigh. If you listen to the accompanying audio tour (strongly advise) the artists provide a context and messages that ring true. Marlene Rubuntja rebuts that sentiment saying: “They better listen because we really have something to say: really good, kind and strong for everyone and for Country.”

Leaving the exhibition, Bard artist Darrell Sibosado reiterated my experience around the process of ceremony and it being one within itself. His description of Ngarrgidj Morr (the proper path to follow) is not about the actual ceremony but the external movement, position, belonging, location, and practice involved in ceremony. I embrace Rubuntja’s thought that art gives us power. It informs, transforms, inspires and heals, and as James Tylor expressed “sometimes you need to feel things to understand them.”

[1] All artist quotes are from the National Gallery of Australia, 4th National Indigenous Art Triennial: Ceremony, 2022, https://nga.gov.au/exhibitions/national-indigenous-art-triennial-ceremony/ More on the earlier triennials–Defying Empire (2017), unDisclosed (2012) and Culture Warriors (2007)–may also be found via the NGA website.

Angelina Hurley is a Gooreng Gooreng, Mununjahli, Birriah & Gamilaraay woman. A writer from Brisbane, Angelina is completing her PhD at Griffith University, writing a television series and thesis on Aboriginal cultural perspectives on humour.